Development of a hydrogen transport infrastructure of its own in Europe: Germany plans for an 1800 km network of pipelines by 2027

Over the last few weeks, several news articles have been published which could jeopardise the fast and proper development of a “Hydrogen Economy” in Europe. The sector, in European terms and quoting the most significant ones, is concerned about three possible obstacles to a proper development of the renewable hydrogen industry within Europe:

- The possible delay in beginning the construction of the dedicated H2Med hydrogen pipeline (also known as BarMar), which will provide the mainspring for transporting renewable hydrogen generated in the Iberian Peninsula (North Africa) to France and other European countries by 2030.

- The regulations for the certification of hydrogen produced in the EU as 100% hydrogen of renewable source, in accordance with the EU’s Renewable Energy Directive (RED) regarding its criteria of progressive integration and temporal and geographical correlation.

- Last but not least, the massive US inflation relief programme contained in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) which includes an investment plan of nearly 370 billion dollars to develop a new industrial ecosystem within strategic clean energy sectors such as renewable hydrogen in the US, is of no less worrying concern.

All these obstacles could mean that Europe may not be the reference market for potential investors and main stakeholders for the complete deployment of hydrogen technologies, which could significantly impact on the EU’s plans and objectives regarding this energy vector.

Draft update of the German 2020 Roadmap on infrastructure deployment

In this new SynerHy article, we review the German government’s plans for the development of an 1800 km network of pipelines (of which 800 km will be new and exclusively hydrogen pipelines and 1050 km will be used by converting the already existing natural gas pipelines into hydrogen pipelines) solely to transport hydrogen in gaseous state by 2027 and the first three large-scale storage caves, supported by public funding. The article is based on a draft that was released last week in Germany at the review of the BMWK’s (Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Protection) Roadmap 2020 for hydrogen development. The national hydrogen strategy undergoes a three-yearly review, although there has been a change of government in Germany since its first launch and it has also taken place at the same time as the current energy price crisis. Europe’s largest economy is seeking to move towards cleaner energy sources and to diversify its supplies, especially after the recent Ukraine invasion and the subsequent difficulties to secure energy supplies on Europe.

According to this draft, a new national hydrogen network company will be founded, which is to “acquire existing hydrogen pipelines and natural gas pipelines that are already operational to convert them” and to implement a development strategy on the basis of a multi-sector system aimed at achieving a hyper-vertebrate hydrogen network by 2030. Meanwhile, new jobs will be created in the field of network planning and regulatory affairs at the responsible administration, in particular at the Federal Network Agency.

The following points are noteworthy for the deployment of hydrogen transport infrastructures:

- The plan focuses on linking the four major industry hubs of the country, mainly the main chemical industries, the refineries, the HUBs of the steel sector and heavy transport (especially maritime and air) through a network of hydroducts, with the objective of achieving an exponential reduction in CO2 emissions.

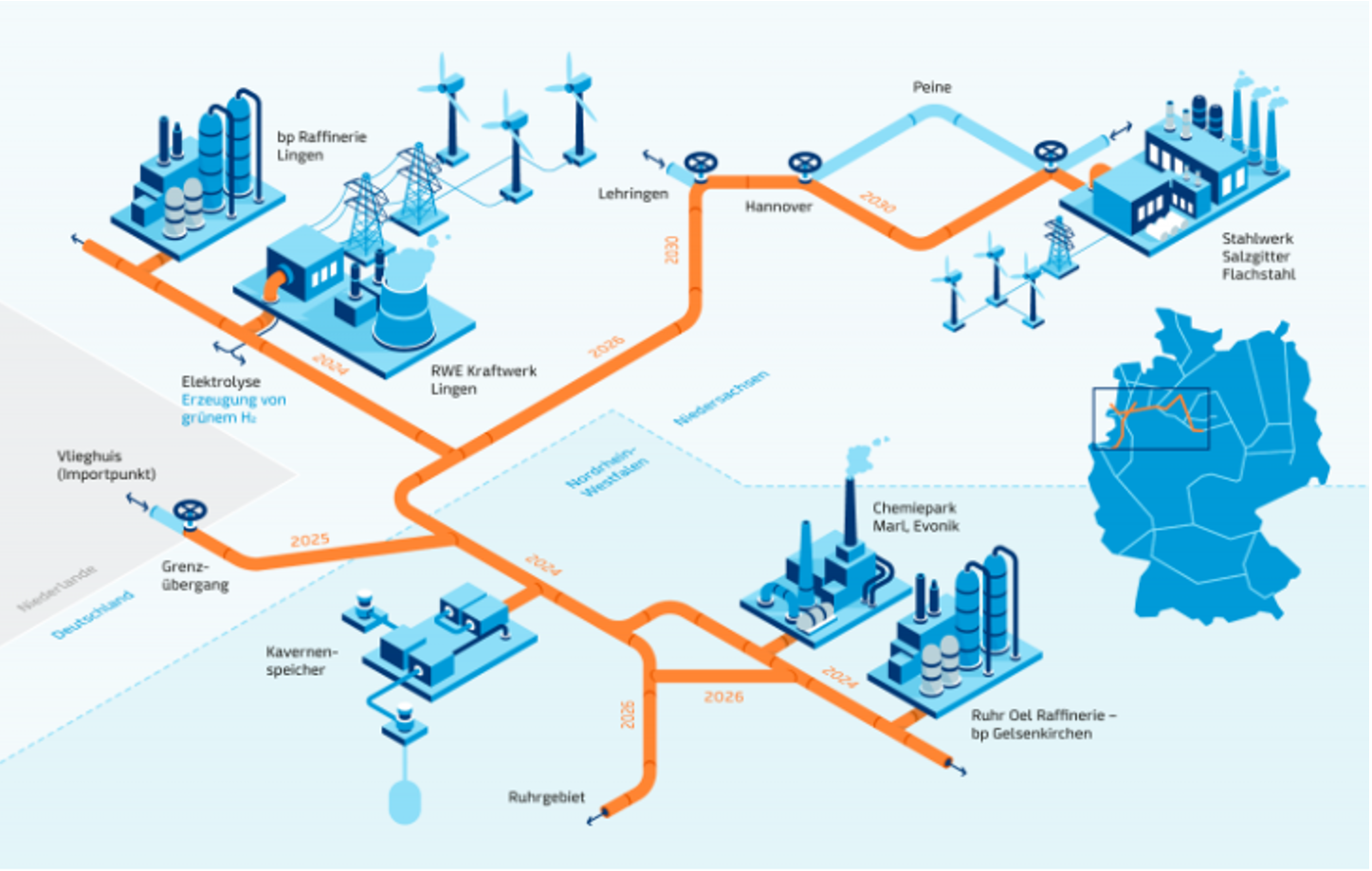

- To begin with, they will rely on the already existing private network of hydroducts located in two hubs, the Ruhr area and the Leipzig area. The know-how on implementing these facilities is the key to their further development. This first stage will be implemented through the GET H2 Nukleus project, which involves companies such as BP, Evonik, Nowega, OGE and RWE (more information).

- An additional 130 km of network will be developed by 2023, linking Lingen to the existing network at Dorsten/Mal and Gelsenkirchen. One of the most important customers of gray hydrogen is the petrochemical industry in the Ruhr valley, and therefore wind energy will be used to generate electrolytic renewable hydrogen to supply it to these industries.

- By 2025, it is planned to connect the network to the Netherlands via the Vlieghuis junction.

- By 2026, the Ruhr valley axis network is planned to be extended by 452 km to link the pipeline to Bremen, Hamburg and Brünsbüttel. The main purpose of this expansion is to use hydrogen in the northern German port environment.

- By 2030, it is expected to link the distribution network to Hanover and Salzgitter, as well as to extend the already existing hydroduct in Southern Lower Saxony up to Berlin to be mainly used in the aerospace industry.

- To link Frankfurt and the south of the country (Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg), the already existing natural gas pipelines will be converted to provide a 300 km network.

The following video shows the roadmap for this development of the German hydrogen infrastructure up to 2030:

Furthermore, on international hydrogen infrastructure, the draft is more specific than the first version of the hydrogen strategy roadmap. The European “backbone” planned for 2030 will be completed by the construction of connection hubs to neighbouring countries, as seen above with the Netherlands. The draft mentions Norway, the UK, Ukraine, Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria as key countries for importing renewable hydrogen. The framework terms for agreements will be defined with these countries in 2023, aiming at the fast-track development of import facilities on the German coast. The new Hydrogen Acceleration Act seeks both to promote the expansion of hydrogen import facilities and to “quickly solve any open questions on the re-financing of such important infrastructures”.

“Different, widely diversified import channels should be opened and new energy dependencies should be avoided,” the draft says. Whereas hydrogen should be imported by pipeline where possible, the BMWK also includes ship deliveries by ammonia, methanol or other hydrogen derivatives in its strategy. The United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Chile and Australia are listed as possible supplier countries for such derivatives. For this purpose, the BMWK draft states that sustainability standards and internationally standardised certification systems for hydrogen and its derivatives will be established.

Review of Germany’s H2 Roadmap

The ambitious new roadmap aims for 10 gigawatts (GW) of hydrogen production capacity through electrolysis by 2030, as stated in the framework agreement of the Socialist-Greens-Liberal coalition government, colloquially known as the traffic light coalition in Germany. Unlike the first strategy in which blue hydrogen (hydrogen produced from the refining of natural gas with CO2 capture) failed to reach a final stage after a long debate, it re-appears again here. The draft quotes “in a transition period, blue hydrogen will also have to be produced and imported”.

In order to achieve the targeted electrolysis capacity within the decade, both onshore and combined offshore wind plants (2.2 GW total installed capacity) are planned to be licensed in 2023, some of which will be funded by the European IPCEI Hydrogen Fund (“Important Project of Common European Interest”). Moreover, an additional 500 megawatts (MW) of installed electrolysis capacity will be tendered between 2023-2028 within the framework of the Offshore Wind Energy Act.

As in the first Roadmap 2022, the BMWK draft only identifies the use of hydrogen where electrification is not possible. For example, in chemical and steel industries, refineries or heavy transport, in which climate protection agreements should be implemented in a short term.

South Africa’s ambitious plans to implement a hydrogen pipeline

To complete the above information of this article focused on the implementation of hydrogen gas transport infrastructure, it is worth mentioning that the South African government has recently made public a 300 billion investment programme within the framework of the National Green Hydrogen Programme, which has been classified as a Strategic Integrated Project (SIP) in accordance with the Infrastructure Development Act of the country.

The development of this hydrogen transport infrastructure is aimed at securing the country’s own supply of clean energy to accelerate its industrial decarbonisation plans, as well as boosting future hydrogen exports to Asia and Europe as derivatives. Moreover, the interest of national companies such as Sasol or PetroSa in developing synthetic fuels is really high.

19 renewable hydrogen projects have already been identified for development, nine of which have been successfully registered at the South African Infrastructure Office, an initiative of the Ministry of Public Works and Infrastructure and the President’s Office to accelerate the investment in infrastructure.

Conclusions

The development of a hydrogen transport network in its gaseous state is key to fostering the mass production of the essential energy carrier required for the future decarbonisation of industry and transport in Europe. Within this article, we intend to show the plans of the biggest European economy towards a coordinated distribution network. As it is shown, the use of already existing private hydroducts is the core for the development of the future network, mainly relying on the bountiful wind energy generated in the north of the country for its electrolytic production. Interconnections with neighbouring countries and import facilities for hydrogen imports in its different derivatives, mainly ammonia, are planned. The aim is to create an 1800 km network to link the country’s two main industrial production hubs (Ruhr and Saxony) to the rest of Germany (also by converting part of the existing natural gas pipeline network).

Low transport costs via pipelines should boost the local production of renewable hydrogen at a competitive price. There are many uncertainties about mass hydrogen production on Europe, such as regulation risks, obstacles from some countries to develop an EU-wide network of exclusively H2 pipelines as well as the prohibitive tax incentives to produce H2 at a very low price in the USA.

By accelerating the goal of an extensive and exclusive hydrogen distribution network, as Germany plans (2027), alongside the promotion and tax incentives for such investments, mainly in Southern Europe, it will contribute to achieving the objectives of industrial decarbonization and the long-desired energy independence within the mid-term using green energies throughout our Continent.

SynerHy, powering net zero

REFERENCES